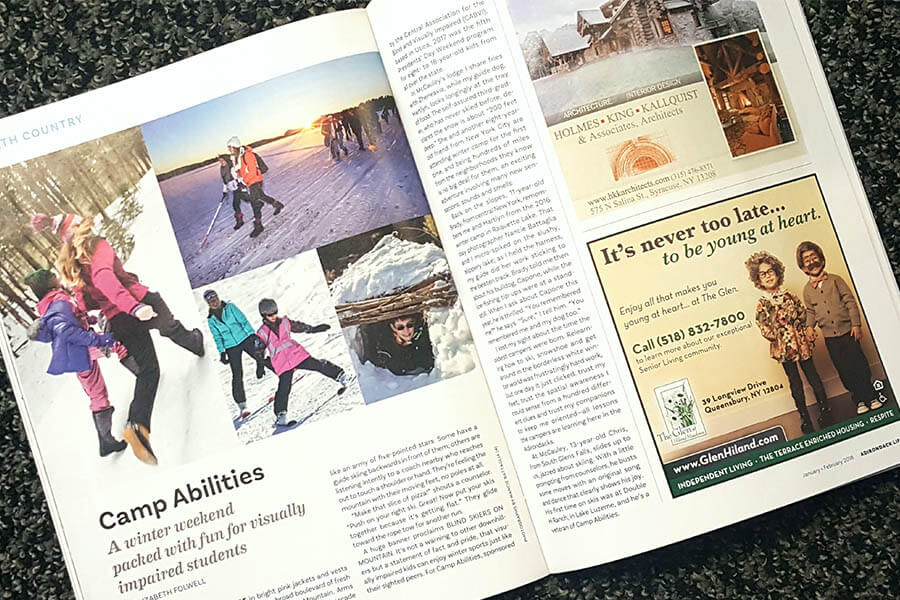

Winter Camp Abilities is Recognized in Adirondack Life Magazine

For the past two years, Elizabeth Folwell, the creative director for Adirondack Life Magazine, worked on a story about our winter Camp Abilities program. Her detail and awareness about what camp is resonates throughout the article. Elizabeth truly captured what Camp Abilities is and what it means to everyone involved! We are extremelygrateful for the time she spent on making this article a home run.

Here is the article:

A dozen kids in bright pink jackets and vests are streaming down the broad boulevard of fresh snow at Old Forge’s McCauley Mountain. Arms outstretched, legs making triangles, they cascade like an army of five-pointed stars. Some have a guide skiing backwards in front of them; others are listening intently to a coach nearby who reaches out to touch a shoulder or hand. They’re feeling the mountain with their moving feet, no poles at all.

“Make that slice of pizza!” shouts a counselor. “Push on your right ski. Great! Now put your skis together because it’s getting flat.” They glide toward the rope tow for another run.

A huge banner proclaims “BLIND SKIERS ON MOUNTAIN.” It’s not a warning to other downhillers but a statement of fact and pride, that visually impaired kids can enjoy winter sports just like their sighted peers. For Camp Abilities, sponsored by the Central Association for the Blind and Visually Impaired (CABVI), based in Utica, 2017 was the fifth President’s Day Weekend program for eight- to 18-year-old kids from all over the state.

In McCauley’s lodge, I share fries with Zheneavia, while my guide dog, Hartlyn, looks longingly at the tray of food. The self-assured third-grader, who has never skied before, declares the snow is about “200 feet deep.” She and another eight-year old friend from New York City are attending winter camp for the first time, and being hundreds of miles from the neighborhoods they know is no big deal for them, an exciting adventure involving many new sensations, sounds and smells.

Back on the slopes, 11-year-old Brady, from central New York, remembers me and Hartlyn from the 2016 winter camp in Raquette Lake. That day photographer Nancie Battaglia and I micro-spiked on the slushy, slippery lake; as I held the harness, my guide did her work sticking to the beaten track. Brady told me then about his bulldog, Capone, while the ice-fishing tip-ups were at a stand still. When I ask about Capone this year, he is thrilled. “You remembered me?” he says. “Sure,” I tell him. “You remembered me and my dog too.”

I lost my sight about the time the oldest campers were born. Relearning how to ski, snowshoe and get around in the borderless white winter world was frustratingly hard work, but one day it just clicked: trust my feet, trust the spatial awareness l could sense from a hundred different clues and trust my companions to keep me oriented-all lessons the campers are learning here in the Adirondacks.

At McCauley, 13-year-old Chris, from South Glens Falls, slides up to us, jazzed about skiing. With a little prompting from counselors, he busts some moves with an original song and dance that clearly shows his joy. His first time on skis was at Double Ranch, in Lake Luzerne, and he’s a veteran of Camp Abilities.

As half the group carves turns on the bunny hill, the others take off on snowshoes. Their guides call out obstacles-an uphill here, a snowbank there-and some campers stride with confidence while others wobble tentatively. There’s a slight wind blowing, not damp or too cold, but the right kind of breeze that helps someone who can’t see recognize when they change direction.

Once everyone has skied, launched and snowshoed, all 27 kids and their 27 counselors and volunteers board the bus headed to Raquette Lake. At twilight, on a path lit by tiki torches, they hike over the frozen lake to their quarters at Camp Huntington, the outdoor education facility owned by the State University of New York at Cortland with historic Great Camp Pine Knot as its centerpiece.

For many of the campers this environment-not just ice and snow but trees, big rocks, a complex of many rustic buildings and a spider web of paths and trails-is not only a challenge but an entirely foreign country. It’s a place defined by risks and new realities, including sharing a cabin with total strangers. “They’re doing a lot of things for the first time,” says 24-year-old Alex Hodkinson, a team leader for older campers. “It’s cold. Maybe they’ve never really been away from home. Here l resolve issues that come up, everything from someone not finding socks under the bunk bed to being overwhelmed by the experience.”

Everyone gathers in the main lodge for meals, open mic sessions like “Care to Share,” where they talk about the new things they’ve tried each day, plus a talent show and a few rounds of whipping and nae-naeing from Silent6’s absurdly popular tune. “How the heck do they pick that one up?” I ask a counselor at lunch. “They just do. They’re wired to learn from their friends,” he says. There are outbursts of song too-the girls belt out the beautiful call and response of Lorde’s “Royals,” countered by the boys’ random chant of “Squirrel! Squirrel! Squirrel!”

Camp Abilities packs a lot into three days, with groups of kids building snow shelters, riding on a dogsled or snowmobile, cross-country skiing and orienteering (with tactile maps and talking compasses). At other communal activities, they discuss everything from careers to fears. These campers set and clear the tables-there are no special accommodations for those kinds of chores. And they help each other find mittens and hats in a jumble of winter clothes, lend support to newbies and form bonds that can last.

Throughout it all, Kathy Beaver, CABVl’s vice-president of rehabilitation services, is everywhere: encouraging kids, advising counselors and checking with instructors who lead specific projects. She explains, “All children, especially children with visual impairment, need to understand that despite adversity they can rise above it, accept the challenge, work through it and move forward. How do we start that process? Including sports and recreation, like at our camps, is one very effective way.”

Beaver says, “There’s no charge to our campers. The money comes from donations and fundraising. The New York State Commission for the Blind chips in under the recreation program, but most comes from projects allied with CABVI. We’re social entrepreneurs: we employ visually impaired people, and their work supports this camp.”

Her agency is an economic powerhouse in Utica, with hundreds of employees and a budget of more than $60 million. There are manufacturing centers in Utica and in Syracuse that package latex gloves used at all air ports in the country. CABVI workers operate switchboards at Veterans Affairs facilities and office-supply stores at six military bases in the eastern U.S.

Camp Abilities has a warm-weather component, at Camp Nazareth, near Woodgate in the southwestern Adirondacks. During the first week of August, about three dozen blind boys and girls swim, hike, ride tandem bikes, paddle kayaks, make s’mores, play softball, perfect their Hula Hooping and hang out under the stars. Some kids need one-on-one guidance from counselors, while others plunge headlong into activities. Many hear loons for the first time, and black flies, mosquitoes and no-see-urns are equal opportunity pests.

One theme at the camps goes beyond recreation and being out doors. There’s a strong component that considers how to prepare visually impaired children and teens for adulthood, higher education and meaningful work. Self-confidence, compassion and curiosity are all pieces of the framework to build success.

“Imagine having a loss of depth perception or being totally blind and developing the courage to climb a rock wall, ski down a mountain or ride a tandem bike,” Beaver says. “You have to overcome fear, trust others, identify character traits within your self that you can rely on, and be brave and daring. And if you can do it once, you can do it again. You can advocate for yourself in the classroom, believe in your dreams, realize your potential and come to understand you are unstoppable. Once we develop strong children who know they can, the rest comes easy.”